INTRODUCTION

Since

the description of a case of gastritis with veno-capillary ectasia as a source of massive haemorrhage by

Rider et al in 19531 many cases have now been recognised. In 1984

Jabari et al2 further defined this condition as ‘watermelon stomach’

based on its endoscopic appearance. This condition appears to be a somewhat

rare entity. This is report of two cases of this disease, both encountered at

Hairmyres Hospital, Glasgow over a period of five years during which 2500

endoscopies were done.

CASE 1

A

64 years old lady was admitted for an episode of melena, which had been

preceded by one month of upper abdominal pain, against a long background of

dyspepsia. On examination she was found to be anaemic.

Investigations showed iron defici-ency anaemia

and haemoglobin (Hb) 10.5 g/dl. Stools were positive for occult blood. Barium

meal and follow through showed persistent narrowing and reduced distensibiltity

in region of gastric antrum. The muscosal pattern however appeared intact.

Upper G.I. endoscopy showed very striking red streaked appearance of antrum

with multiple small raised red lesions. Biospy from the lesion showed small

collection of telangiectatatic capillaries lined by prominent endothelial cells

and one vessel contained thrombus. Biospy from gastric area showed mild to

moderate active chronic gastritis. While she was under observation her stools

continued to be positive for occult blood. Her Hb fell to 9.2g/dl. She was

transfused. Repeat endoscopy showed essentially similar features. She was

subjected to Antrectomy and Billroth I anastomosis. Gross biopsy specimen of

pyloric antrum showed prominence of rugae with red streaks over the tips of

gastric folds. Small pectial foci were seen in mucosa. There were small groups

of blood vessels in submucosa. Histology showed several small groups of

superficially located dilated capillaries, some of which contained fibrin thrombus.

There was focal fibro-muscular proliferation in the lamina propria. The

submucosa was oedmatous. There were groups of ectatic venous channels. Her

haemoglobin remained stable at around 14g/dl after surgery during two years

follow up.

CASE2

A

73 years old woman was admitted for weight loss, malaise, dyspnoea and ankle

swelling. On examination she was anaemic. She also had atrial fibrillation and

signs of early congestive cardiac failure.

Her investigation showed iron deficiency anaemia due

to chronic blood loss and Hb 7.1g/dl. Stools were positive for occult blood.

ESR was high. Immunoglobulins showed very high IgM 8.47g/l (91%mean normal

adult value). Liver Function Tests showed mild elevation of ALT (45.2). Barium

meal and enema were normal.

She was treated for congestive cardiac failure. She

was transfused. As her symptoms remained unchanged with persistently low Hb, an

upper GI endoscopy was done to exclude primary gastric lesion.

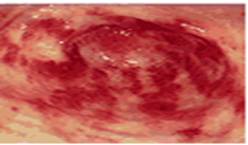

The

gastric antrum was grossly abnormal with typical appearance of watermelon

stomach (Figure1).

Figure 1: An upper endoscopy reveals

longitudinal erythematous stripes resembling stripes of a water melon

Figure 1: An upper endoscopy reveals

longitudinal erythematous stripes resembling stripes of a water melon

Biopsy

from the lesion showed small group of telangatatic vessels some of which

contained thrombus in lamina propria. In addition fibromuscular element was

present in mucosa.

She was advised surgery, which

she refused. She is still being followed up and remains rather tired and her

last checked Hb was 9.4g/dl

DISCUSSION

In

an elderly patient, especially in females persistent iron deficiency anaemia

with hypochlorydria or achlorhydria should warrant the diagnostic possibility

of gastric vascular ectasia. The mean age of presentation is 69.1 years (range

42-89 yrs). Patient most commonly present with chronic occult blood loss or

recurrent acute haemorrhage.3,4 The common clinical presentations

are iron deficiency anaemia (88%), Faecal Occult Blood (FOB) positive (42%),

Melena (15%), hematemesis (3%) and rarely hematochezia (1%).5 The

occult bleeding is transfusion dependent with a mean of 10 units over a

12-month period.

The aetiology of this condition remains unknown; one

theory being that water melon stomach is caused by recurrent episodes of antral

mucosal prolapse into pylorus that leads to mucosal trauma and ischemia.

Other conditions are associated with this condition.

In one series3 the most common associated disorders were Raynaud’s

phenomenon (31%) and sclerodactely (18%). Other associated conditions include

hypothyroidism, primary biliary cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus and autoimmune

liver disease.3-7

The diagnostic endoscopic findings are both uniform

and remarkably characteristic, these include longitudinal rugal folds

transforming the antrum and converging on pylorus, each containing a visible

convoluted column of vessels, the aggregate resembling the stripes of water

melon.2

Other features

include gastritis with evidence of mucosal prolapse. Conventional radiology is

often non-specific. Both gross appearance of resected antrum and microscopic

picture is characteristic. The resected specimen shows thickened mucosa with

torturous submucosal venous channels. Microscopic picture may show dilatation

of muscoal capillaries with focal thrombosis and fibromuscular hyperplasia of lamina

propria1,2,

The therapeutic options are numerous for this

condition and need to be individualised. Improvement of anaemia with out

further iron supplementation following surgery in patients including one of our

own case (Case1) suggest that the most appropriate treatment for this condition

is antrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis, but their is mortality of 7.4%8

associated with this operation.

Endoscopic therapy has been shown to be effective

with a minimal mortality. Endoscopic therapy, including the NDYAG laser, argon

laser, heater probe, bipolar therapy have been effective as a treatment. The

number of endoscopic sessions needed varied between 3-4 sessions over period of

4-12 months.3,6,7,9-11

Pharmacological agents like prednisone,2,12

prednisolone,13,14 estrogen-progesterone preparations13

have been used with various success rates. Octreotide was not shown to be

effective.15

In conclusion, Watermelon stomach is an increasingly

recognisable cause of persistent acute or occult gastrointestinal bleeding,

especially in elderly women. Usually presenting as severe iron deficiency

anaemia and occult or overt gastrointestinal blood loss. Diagnosis is

endoscopic, with characteristic appearance of watermelon like linear stripes in

antrum. Histology is rarely needed to confirm the diagnosis. The important

thing is to recognise the characteristic lesion and carry out appropriate

endoscopic procedure, leading to healing of the lesion with significant

improvement in the anaemia and a reduction in the need for blood transfusions.

REFERENCE

1.

Rider

JA, Koltz AP, Kirsner JB. Gastritis with veno-capillary ectasia as source of

massive gastric hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1953:24;118-23.

2.

Jabbari

M, Cherry R, Lough JO, Daly DS, Kinnear DG, Goresky CA. Gastric antral vascular

ectasia: the watermelon stomach. Gastroenterology 1984; 87:1165-70.

3.

Gostout

CJ, Viggiano TR, Ahlquist DA, Wang KK, Larson MV, Balm R. The clinical and

endoscopic spectrum of the watermelon stomach. J Clinical Gastroenterol 1992;

15:256-63.

4.

Merrett

MN, Machet D, Ring J, Desmond PV, Martin CJ. Watermelon stomach: an unusual

cause of chronic gastrointestinal blood loss. Aust N Z J Surg 1991;61:393-96.

5.

Gretz

JE, Achem SR. The watermelon stomach: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and

treatment. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93:890-5.

6.

Gostout

CJ, Ahlquist DA, Radford CM, Viggiano TR, Bowyer BA, Balm RK. Endoscopic laser

therapy for watermelon stomach. Gastroenterology 1989;96:1462-5.

7.

Tsai

HH, Smith J, Danesh BJ. Successful control of bleeding from gastric antral

vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) by laser photocoagulation. Gut 1991;

32:93-4.

8.

Borsch

G. Diffuse gastric antral vascular ectasia: the "watermelon stomach"

revisited. Am J Gastroenterol 1987; 82:1333-4.

9.

Bjorkman

DJ, Buchi KN. Endoscopic laser therapy of the watermelon stomach. Lasers Surg

Med 1992; 12:478-81.

10. Frager JD, Brandt LJ, Frank MS, Morecki

R. Treatment of a patient with watermelon stomach using transendoscopic laser

photocoagulation. Gastrointest Endosc 1988; 34:134-7.

11. Watson M, Hally RJ, McCue PA, Varga J,

Jimenez SA. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) in patients

with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39:341-6.

12. Kruger R, Ryan ME, Dickson KB, Nunez JF.

Diffuse vascular ectasia of the gastric antrum. Am J Gastroenterol 1987;

82:421-6.

13. Moss SF, Ghosh P, Thomas DM, Jackson JE,

Calam J. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: maintenance treatment with

estrogen-progesterone. Gut 1992; 33:715-7.

14. Rawlinson WD, Barr GD, Lin BP. Antral

vascular ectasia – the "watermelon" stomach. Med J Aust

1986;144:709-11.

15. Barbara G, De GR, Salvioli B,

Stanghellini V, Corinaldesi R. Unsuccessful octreotide treatment of the

watermelon stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 26:345-6