In medical parlance 'stress' is defined as a perturbation of the body's homeostasis. This demand on mind-body occurs when it tries to cope with incessant changes in life. Stress is a concept invented in the 1930s by Dr. Hans Selye.1 Dr. Selye admitted that stress is an abstract concept, and he admitted that stress has never been adequately defined. Dr. Selye's own definition of stress is the non-specific response of the body to any demand.2

Confusion about the concept of

stress:

Dr. Selye erred when he named his creation "stress."3 He had meant to make an analogy with the mechanical engineering concepts of stress and strain. Stress is the measure of a force that changes the length of an object (like a beam or strut), and strain is the resulting deformation of that object. Stress in the health-context, therefore, is a metaphorical allusion to strain: Dr. Selye meant to refer to a reaction to outside forces acting on the body, rather than to the outside forces themselves. So he should have named his conceptual mechanism "strain" rather than "stress. At one point or the other everybody suffers from stress.

"Nothing gives one person so much advantage over another as to remain always cool and unruffled under all circumstances." —Thomas Jefferson

There seems to

be a wide variety of life experiences, which result in some form of stress,

fear, anxiety, or psychosomatic illness.

Causes of Stress

Environmental

factors and processes

·

Changes,

such as sudden trauma, several big crises, or many small daily hassles, cause

stress.4 Intense stress years earlier, especially in childhood, can

predispose us to over-react to current stress.

·

Events,

such as barriers and conflicts that prevent the changes and goals we want,

create stress.4 Having little control over our lives, e.g. being

"on the assembly line" instead of the boss, contrary to popular

belief, often increases stress and illness.

·

Many

environmental factors, including excessive or impossible demands, noise, boring

or lonely work, stupid rules, unpleasant people4, etc., cause

stress.

·

Conflicts

in our interpersonal relationships cause stress directly and can eventually

cause anxieties and emotional disorders.5

Constitutional or physiological

processes

The genetic, constitutional, and intrauterine factors6

influence stress. Some of us may have been born “nervous” and “grouches”

Learning processes

·

Having a

"bad experience" causes us to later be stressed in that situation,

i.e. pairing a neutral stimulus (situation) with a painful, scary experience

will condition a fear response to the previously neutral stimulus. (classical

conditioning)

·

Fears and

other weaknesses may yield payoffs; the payoffs (like attention or dependency)

cause the fear to grow. (operant conditioning)

Summary

of the Effects of Stress and Anxiety

The effects or consequences of stress are also

numerous; they are both positive and negative.

First, the desirable results:

1.

We need and

enjoy a certain level of stimulation...a certain number of thrills. It would be

boring if we had no stresses and challenges. Some people even make trouble for

themselves to keep from getting bored.

2.

Stress is a

source of energy that can be directed towards useful purposes. How many of us

would study or work hard if it were not for anxiety about the future?

3.

Mild to

moderate anxiety makes us more perceptive and more productive, e.g. get better

grades or be more attentive to our loved ones.

4.

By facing

stresses and solving problems in the past, we have learned skills and are

better prepared to handle future difficulties.

5.

Anxiety is

a useful warning sign of possible danger--an indication that we need to prepare

to meet some demand and a motivation to develop coping skills.

The negative effects or consequences of

stress and anxiety

1.

Several

unpleasant emotional feelings are generated--tension feelings of inadequacy,

depression, anger, dependency and others.

2.

Preoccupation

is with real or often exaggerated troubles--worries, concerns about physical

health, obsessions, compulsions, jealousy, suspiciousness, fears, and phobias.

3.

Most

emotional disorders are related to stress; 7 they either are caused

by stress and/or cause it or both. Interpersonal problems can be a cause or an

effect of stress--feeling pressured or trapped, irritability, fear of intimacy,

sexual problems, feeling lonely, struggling for control, and others.

4.

Feeling

tired is common--stress saps our energy.

5.

Many

bad habits (e.g. procrastination and much wasted time are attempts to handle

anxiety. They may help relieve anxiety temporarily but we pay a high price in

the long run.

6.

.Psychosomatic

ailments result from stress--a wide

variety of disorders are caused by psychological factors, maybe as much as 50%

to 80% of all the complaints treated by physicians. Stress can cause headaches, irritable bowel syndrome,

eating disorder, allergies, insomnia, backaches, frequent cold and fatigue to

diseases such as hypertension, asthma, diabetes, heart ailments, migrane,

grave’s ophthalmology and even cancer.8, 9

7.

Stress/stresssful

life events can precipitate a number of psychiatric disorders including conversion disorder10

adjustment disorder11 acute stress reaction, and post- traumatic stress disorder,12 generalized anxiety

disorder13,14, depression15

and somatization disorder.16

8.

A

study has shown 96% of subjects reported dissociative ( conversion) symptoms in

response to acute stress during U.S. Army survival training.17 Another study found that

people experiencing acute stress disorder in response to a traumatic

experience have stronger ability to experience dissociative phenomena than

people who do not develop acute stress disorder.18 Severe levels of posttraumatic stress and

depressive reaction were found in adolescents in two cities of Nicaragua

affected by a hurricane.19 . Similarly after another stressful

incidence (series of sniper shooting in

9.

High stress

almost always interferes with one's performance (unless it is a very simple

task). It causes inefficiency at school and on the job, poor decision-making,

accidents, and even sexual problems. Anxiety and fear causes us to avoid many

things we would otherwise enjoy and benefit from doing. People avoid taking

hard classes, trying out for plays or the debate team, approaching others,

trying for a promotion, etc. because they are afraid.

Optimum levels of

stress

Experts tell us that stress, in moderate doses, is necessary in our life. Stress responses are one of our body's best defence systems against outer and inner dangers. In a risky situation (in case of accidents or a sudden attack on life), body releases stress hormones that instantly make us more alert and our senses become more focused. The body is also prepared to act with increased strength and speed in a pressure situation. It is supposed to keep us sharp and ready for action. Research suggests that stress can actually increase our performance. Instead of wilting under stress, one can use it as an impetus to achieve success. Stress can stimulate one's faculties to delve deep into and discover one's true potential. Under stress the brain is emotionally and biochemically stimulated to sharpen its performance.

Now I will explain the linkage between stress and performance, and show how you can ensure that you perform at your best by optimising stress levels.

The approach to optimising stress depends on the

sort of stress being experienced. Strategies to deal with short term stresses

focus on managing adrenaline to maximise performance. Short-term stresses may be

difficult meetings, sporting or other performances, or confrontational

situations. With long term stress, fatigue and high adrenaline levels over a

long period can seriously reduce your performance. Optimising long term stress

concentrates on management of fatigue, health, energy and morale. Naturally

there is some element of overlap between these.

Short term stress

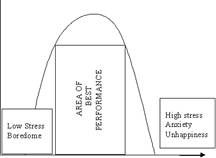

The graph in Fig: 1 shows the relationship between stress

and the quality of performance when you are in situations that impose

short-term stress: Where stress is low, you may find that your performance is

low because you become bored, lack concentration and motivation. Where stress

is too high, your performance can suffer from all the symptoms of excessive

short-term stress. In the middle, at a moderate level of stress, there is a

zone of best performance. If you can keep yourself within this zone, then you

will be sufficiently aroused to perform well while not being over-stressed and

unhappy. This graph, and this zone of optimum performance, are different shapes

for different people. Some people may operate most effectively at a level of

stress that would leave other people either bored or in pieces. It is possible

that someone who functions superbly at a low level might experience difficulties

at a high level. Alternatively someone who performs only moderately at low

level might perform exceptionally under extreme pressure.

![]()

Stress

Fig: 1 The Relationship Between Stress

And Performance

Long term stress

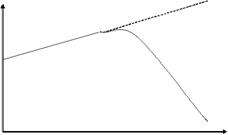

The problems of long term, sustained stress are more

associated with fatigue, morale and health than with short-term adrenaline

management. The graph as shown in Fig: 2 show the way in which performance can

suffer when you are under excessive long-term stress:

![]()

Healthy Hardwork

![]()

Fig: 2 The Relationship between long term stress

and performance

Fig: 2 The Relationship between long term stress

and performance

The graph shows stages that you may go through

in response to sustained levels of excessive stress. During the first phase you

will face challenges with plenty of energy. Your response will probably be

positive and effective. After a period of time you may begin to feel seriously

tired. You may start to feel anxious, frustrated and upset. The quality of your

work may begin to suffer. As high stress continues you may begin to feel a

sense of failure and may be ill more frequently. You may also begin to feel

exploited by your organisation. At this stage you may start to distance

yourself from your employer, perhaps starting to look for a new job.

If high levels of stress continue without relief

you may ultimately experience depression, burnout, nervous breakdown, or some

other form of serious stress related illness.

Different people may move between these stages

with different speeds under different stress conditions.

Strategies for Coping with Stress

There are three basic strategies for coping with stress21,22,

(other than ignoring or denying

your problems). These are:

1. The Band-Aid

Approach--using alcohol,

drugs (prescription or illegal), cigarettes, food, sex, or anything else to

temporarily relieve the symptoms of "stress." While these coping

strategies "work" in the short-run, they have harmful long-term

effects, which make them undesirable.

2. The Stress

Management Approach---using

diet, exercise, meditation, biofeedback, behavioural techniques or other

relaxation exercises to cope with your "stress23,24."

While these coping strategies have definite advantages over band-aid methods,

they still focus mainly on just the symptoms of your problems.

i.

Eat

sensibly. A well balanced diet will improve your ability to respond to stress

appropriately.

ii.

Tiredness

Sleep-make sure you get

an adequate sleep each night.

iii.

Exhaustion

Tiredness. Cut down on

stimulants—caffeine and nicotine don’t help.

iv.

Ill-Health Breakdown

Exercise-Aerobic exercise

can reduce anxiety by up to 50 %.

v.

Relax-Learn

and practice relaxation techniques regularly.

vi.

Take time

off---Go for a walk, listen to music, take a bath .you will feel better.

vii.

Prioritise-If

you have multiple stress factors (deadlines, financial worries illness

problems) concentrate on the ‘must ‘first and put ‘shoulds' to the back of your

mind for the moment.

3.

The

Ideal Approach-----------making

stress disappear, quickly and naturally, by modifying or correcting its

underlying causes. While this is by far the best way to deal with problems in

life, most people fail to use this approach because they incorrectly understand

what causes their stress to occur.

In recent years, new insights about the causes

of human stress have emerged.25,26 These new insights focus on the

difference between obvious and non-obvious causes. Obvious causes of stress

include the things that happen to us and around us--i.e. the things we easily

see. Non-obvious causes include conversations and behaviour patterns that

become triggered within our bodies. These include expectations, judgements,

evaluations, needs for control, needs for approval, and many others.

The more

you learn to recognise and deal with these non-obvious causes of your problems,

the less stress, tension, and physical ailments you will likely experience.

References

1.

Mason

JW. A historical view of the stress field. Part 1. J. Human Stress 1 1975;1: 6-12

2.

Selye

H. Stress in Health and Disease.

3.

Selye

H. Confusion and controversy in the stress field. J. human . Stress 1975;

4.

Pasnau RO. Coping

With Stress: Effective People and Processes. Am J Psychiatry

2002;159:1451-a-1452-a.

5.

Selye

H. The Stress of Life.

6.

Selye

H. A Syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. Nature 1936;138:32.

7.

Brown

GW, Haaris TO, Peto J. life events and psychiatric disorders: the nature of

causal link. Psychological medicine 1973;3:159-176

8.

Weiner

H. Psychobiology and human disease.

9.

Alexander

F. Psychosomatic Medicine. Newyork Norton; 1950.

10.

Lempert

T, Schmidt D. Natural history and outcome of psychogenic seizures: A

clinical study in 50 patients. J Neurol

1990; 237:35-7.

11.

Newcorn JH, Strain JJ. Adjustment

disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry 1991; 31: 318-23.

12.

Shore

JH, Vollemer WM, Tatum El. Community patterns of post-traumatic stress

disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental disease 1989; 177:681-85

13.

Brown

GW, Harris TO. Aetiology of anxiety and depressive disorder in an inner city

pouplation. Early adversity. Psych Med 1993;23:143-54

14.

Finlay-Jones

R, Brown GW. Types of stressful life events and the onset of anxiety and

depressive disorder. Psychological medicine 1981;11:803-16

15.

Brown

GW, Harris TO. Stressor, vulnerability,

and depression: a question of replication. Psych Med 1986; 16:739-44.

16.

Ladwig

KH, Mitagg GH, Erazo N, Gundel H.

Identifying somatization disorder in a population based health examination

survey: Psychosocial burden and gender differences. Psychosomatics 2001;42:511-8.

17.

Morgan

CA, Hazlat G, Wang S, Richardson EG, Schnurr P, South SH. Symptoms of dissociation

in humans experiencing acute

uncontrollable stress: A prospective investigation. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:

1239-47.

18.

Bryant RA, Guthrie RM, Moulds ML. Hypnotizability in Acute stress

disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:600-4.

19.

Goenjian

Ak, Molina L, Steinberg AM, Fairbank LA, Alvarez ML, Goenjian HA, et al.

Posttraumatic stress and Depressive reactions among Nicaraguan adolescents

after hurricane Mitch. Am J Psychiatry;2001;58:788-94.

20.

Greiger

TA,

21.

Moore E. Coping with Grave’s disease. [Online] 1996. [cited 2004

Jan 14]. Available from http:// www.

suite101.com/article.cfm/graves_disease/86787.

22.

Pitzer R. Coping with Parental Stress. [Online] 1998. [cited 2004 Jan 14]. Available

from http: // www. extension.umn.edu/distribution/familydevelopment/

DE 7269.html.

23.

Smaritans . Stress busting [Online] 2004 [cited 2004 Feb 12]

Available from URL http://www.smaritans.org

24.

Baum A, Herberman

H, and Cohen L. Managing stress and managing illness: Survival and quality of

life in chronic disease. Journal of clinical psychology in medical settings,

2002; 2(4): 309-333.

25.

Charney

DS. Psychobiological Mechanisms of Resilience and Vulnerability:

Implications for Successful Adaptation to Extreme Stress. Am

J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 195-216.

26.

Flach F. Treatment of Stress Response Syndromes. Am. J.

Psychiatry 2004; 161: 182-186.