INTRODUCTION

Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome (PLS)

is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized

by hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles and severe destructive periodontal

disease affecting both the primary and permanent teeth. This

case report describes a case of PLS classic clinical features and brief review the relevant literature.

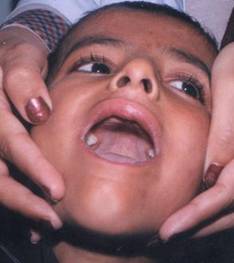

Figure-1:

Absence of upper and lower incisor teeth.

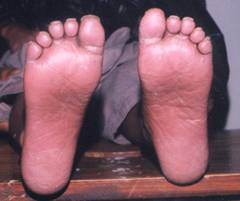

Figure-2: Yellow

colored hyperkeratotic areas on soles

Figure 3

Figure-4

Figure

5

A six year old male child born of cousingeous parents presented to us with redness and

peeling off of skin of hands and feet, cough, redness and discharge from eyes

and ear, pain for last 20 days. He had exacerbations and remissions of the skin

lesions and multiple infections since early childhood. He had normal outcome at

birth and had normal developmental milestones till age of three. During 3rd

year of his life he started developing fissures in skin of palms and soles that

resulted in peeling off of skin leaving red thin skin underneath. He repeatedly

contracted systemic infections. He had cough for last one month that was dry

initially and later on became productive. He used to get bouts of cough and

diagnosed as having pertussis. He complained of

earache that was diagnosed as otitis media. Similarly

he had bilateral purulent conjunctivitis. On examination of oral cavity his

upper incisors, upper lower canines, upper and lower molars were absent (Figure

1). His deciduous teeth started falling off at age of three years and only his

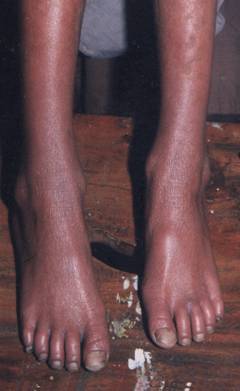

lower incisors erupted again that too became loose. Skin of both palms and

soles was peeling off and underlying skin was red and shiny suggestive of keratoderma (figures 2,3,4,5). The

fingers were pointed and gave a clawed appearance. On eye examination he had

bilateral congested conjunctivae with purulent discharge. Ear examination

revealed bulging red tympanic membrane suggestive of bilateral acute otitis media. On chest auscultation he had bilateral rhonchi. Rest of the systemic examination was normal. On

family history there were no similar disorders in family.

Routine hematological examination revealed Hb% of 10.0 g/dl, total leukocyte count of 9200 and ESR was

20 mm/hour. Urine routine examination showed 15-20 pus cells and 3-4 red blood

cells suggestive of urinary tract infection. Rest of the biochemical

investigations were within normal limits.

Discussion

Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, or keratosis palmoplantaris with periodontopathia (PLS, MIM 245000), is inherited as an autosomal

recessive trait, affecting children between the ages 1-4 years.1,2

It has a prevalence of 1-4 cases per million persons.2 Males and

females are equally affected and there is no racial predominance.3 PLS

is characterized by palmoplantar keratodermas,

psoriasiform plaques of the elbows and knees,

periodontal disease with resultant premature loss of deciduous and permanent

teeth, and intracranial calcifications.4 These keratotic

plaques may occur focally, but more often involve the entire surface of the

palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar keratosis, varying from mild psoriasiform

scaly skin to overt hyperkeratosis, typically develops within the first three

years of life.6 Often, they are associated hyperhidrosis of the palms and soles resulting in a

foul-smelling odor.2 The findings may worsen in winter and be associated

with painful fissures.7 The development and eruption of the

deciduous teeth proceeds normally, but their eruption is associated with

gingival inflammation and subsequent rapid destruction of the periodontium. The resulting periodontitis

characteristically is unresponsive to traditional periodontal treatment

modalities and the primary dentition is usually exfoliated prematurely by age 4

years. After exfoliation, the inflammation subsides and the gingiva

appears healthy. However, with the eruption of the permanent dentition the

process of gingivitis and periodontitis is usually

repeated and there is subsequent premature exfoliation of the permanent teeth,

although the third molars are sometimes spared.8,9 The etiology of

periodontal disease was explained with juvenile periodontitis

due to infection with Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans rather than immunologic dysfunction

or anatomic defects.5 Both

the deciduous and permanent dentitions are affected; resulting in premature

tooth loss. Most PLS patients display both periodontitis

and hyperke-ratosis. Some patients have only palmoplantar keratosis or periodontitis, and in rare individuals the periodontitis is mild and of late onset.6

In addition to the skin and oral findings, patients may have decreased neutrophil, lymphocyte or monocyte

functions and an increased susceptibility to bacteria, associated with

recurrent pyogenic infections of the skin.10

Histologically, the skin lesions of PLS have not been

well-characterized in the literature. Reported findings have consisted of

hyperkeratosis, occasional patches of parakeratosis, acanthosis, and as light perivascular

inflammatory infiltrate4.

The PLS locus has

been mapped to chromosome 11q14–q21 with an almost total loss of cathepsin C activity in PLS patients and reduced activity

in obligate carriers11-13.

The cathepsin C gene encodes a cysteine-lysosomal

protease also known as dipeptidyl-peptidase

I, which functions to remove dipeptides from

the amino terminus of the protein substrate. It also has endopeptidase

activity. The cathepsin-C gene is expressed in

epithelial regions commonly affected by PLS such as palms, soles, knees, and

keratinized oral gingiva. It is also expressed at

high levels in various immune cells including polymorphonuclear

leukocytes, macrophages, and their precursors.14,15

All PLS patients are homozygous for the same cathepsin-C

mutations inherited from a common ancestor. Parents and siblings, heterozygous

for cathepsin C mutations do not show either the palmoplantar hyperkeratosis or severe early onset periodontitis characteristic of PLS8.

A multidisciplinary approach is important

for the care of patients with PLS. The skin manifestations of PPK are usually

treated with emollients7. Oral retinoids

such as acitretin, etretinate,

andisotretinoin were reported to be beneficial for

both dental and cutaneous lesions of PLS. Retinoid

treatment may end up with normal dental development if started during eruption

of permanent teeth.16 The periodontitis in PLS is usually difficult to control.

Effective treatment for the periodontitis includes

extraction of the primary teeth combined with oral antibiotics and professional

teeth cleaning. It is reported that etretinate and acitretin modulate the course of periodontitis

and preserve the teeth. A course of antibiotics should be tried to control the

active periodontitis in an effort to preserve the

teeth and to prevent bacteremia and subsequently pyogenic liver abscess.17

References

1.

Hart TC, Shapira L. Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. Periodontol 2000 1994;6:88-100.

2.

Gorlin RJ, Sedano H, Anderson VE. The syndrome of

palmar-plantar hyperkeratosis and premature periodontal destruction of the

teeth. J Pediatr 1964;65:895-908.

3.

Cury VF, Costa JE, Gomez RS, Boson WL, Loures CG, De ML. A

novel mutation of the cathepsin C gene in Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. J Periodontol 2002; 73(3):307-12.

4.

Landow RK, Cheung H, Bauer M. Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. Int J Dermatol 1983;22:177-9.

5.

Bach JN, Levan NE. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. Arch Dermatol1968;97:154-8

6.

School of Biological Sciences, University of Manchester, Stopford Building, University of Manchester, Manchester,

UK.

7.

Siragusa M, Romano C, Batticane N, Batolo D, Schepis

C. A new family with Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome: effectiveness of etretinate treatment. Cutis 2000;65(3):151-5.

8.

Hart TC, Hart PS, Bowden DW, Michalec MD, Callison SA, Walker SJ, et al.

Mutations of the cathepsin C gene are responsible for

Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. J Med Genet 1999;36(12):881-7.

9.

Haneke E. The Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome: keratosis

palmoplantaris with periodontopathy. Report of a case and review of the cases

in the literature. Hum Genet 1979;51(1):1-35.

10. Giansanti JS, Hrabak RP, Waldron CA. Palmar-plantar hyperkeratosis and concomitant periodontal

destruction (papillon-Lefèvre syndrome). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1973;36(1):40-8.

11. Department of Immunology and

Infectious Diseases, New Children's Hospital, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia

12. Department of Pediatric

Dentistry, Westmead Hospital Dental Clinical School, Westmead, New South Wales,

Australia.

13. Department of Oral Diagnosis

and Periodontology, Eins-Shams University, Cairo, Egypt.

14. Angel TA, Hsu S, Kornbleuth

SI, Kornbleuth J, Kramer EM. Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome: a case report of four

affected siblings. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46(2 Suppl Case Reports):S8-10.

15. Toomes C, James J, Wood AJ, Wu CL, McCormick D,

Lench N, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cathepsin C gene result in

periodontal disease and palmoplantar keratosis. Nat Genet 1999;23(4):421-4.

16. Eickholz P, Kugel B, Pohl S, Naher H, Staehle HJ.

Combined mechanical and antibiotic periodontal therapy in a case of Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. J Periodontol 2001;72:542-9.

17. Almuneef M, Al Khenaizan S, Al Ajaji S, Al-Anazi A.

Pyogenic liver abscess and Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome: not a rare association.

Pediatrics 2003;111(1):e85-8.